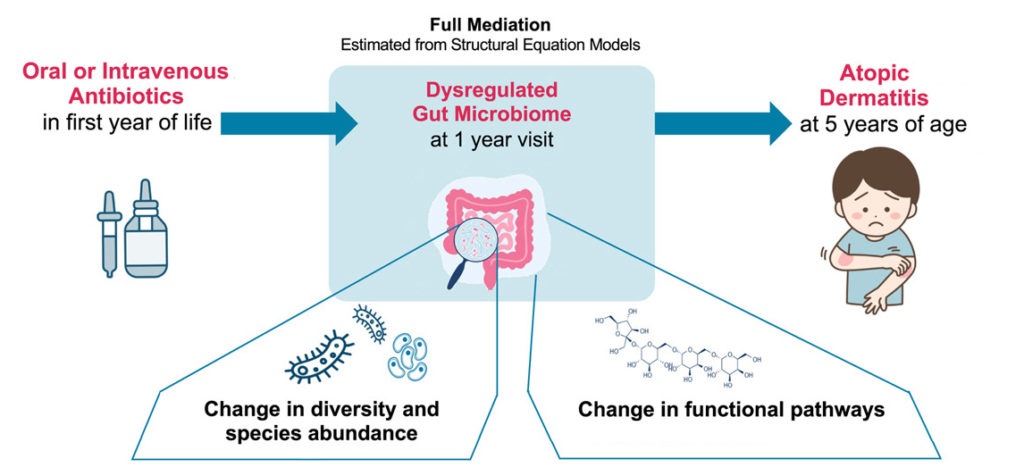

New research from CHILD found that babies who are exposed to antibiotics in the first year of life are more likely to later develop atopic dermatitis, or eczema. The connection lies in the bacteria of the infant’s gut: its microbiome, which can be disrupted by antibiotic use.

Because eczema is often the starting point for the development of other allergic disorders, this finding points to a possible mechanism, and thus to possible preventive strategies, for allergic disease more generally.

In this study, published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (JACI), researchers in the labs of CHILD Director Dr. Padmaja Subbarao (SickKids and UofT) and Co-Director Dr. Stuart Turvey (UBC and BC Children’s Hospital) started by further investigating an association revealed by earlier research. They had noticed that children who experienced severe respiratory infections as babies had a higher risk of later developing eczema, but they weren’t sure why. (Of the 106 CHILD participants who had severe respiratory infections in their first 18 months of life, over 22% developed eczema by age five; of CHILD participants who had no such infections, only 13% later developed eczema.)

“Because the link between early respiratory infection and eczema was robust, even when we took into account other factors that influence eczema risk, it suggested to us that either the infection or its treatment was responsible,” comments the study’s co-lead author Maria V. Medeleanu, a PhD candidate at UofT and SickKids.

When they looked closely at the role of antibiotic use, they found this to be the key factor: “Using mediation modeling, we detected that systemic antibiotic use had a significant mediating effect on later eczema development,” adds co-lead author UBC PhD candidate Courtney Hoskinson, “while the direct effect of the respiratory infections themselves was insignificant.”

To explore this association of antibiotic use and eczema risk further, they then looked at all the 2,484 kids in CHILD who had been assessed for eczema at age five. Among these kids, they found that there was a high overlap between the 365 kids diagnosed with eczema at age five and the 516 who had received oral or intravenous treatment with antibiotics—for any reason, whether respiratory infections or other health issues—during their first year of life. In other words, they found that early antibiotic use was consistently linked to a higher eczema risk, suggesting that it was the antibiotics, not the infection, that was making the difference.

Previous CHILD research had already shown that systemic antibiotics taken in early life can have unanticipated negative effects on our health because of their impact on our microbiome—the community of bacteria and other microorganisms that live in and on our bodies, and especially in our digestive tract, or gut. CHILD data had also revealed that the state of the microbiome in the first year of life is especially important to long-term health.

Knowing this, the researchers then analyzed the stool samples that had been collected at one year of age from the kids whose health data they were comparing. They wanted to see if different microorganisms lived in the guts of kids exposed to antibiotics and who later developed eczema, compared to other kids. They found there was a distinct pattern in the abundance of different types of gut microorganisms and their functions among kids who had been exposed to antibiotics in their first year and those diagnosed with eczema at age five.

“This shared microbiome ‘signature’ suggests that the use of antibiotics before one year has a strong indirect effect on the development of atopic dermatitis, through the changes these antibiotics cause in the one-year gut microbiome,” says co-senior author Dr. Turvey.

“Interestingly, antibiotic use after age one did not have the same impact; kids exposed only to antibiotics later in life, even at two years, did not have a significantly different eczema risk compared to kids with no antibiotic exposure,” adds Maria V. Medeleanu.

“It seems our first year represents a particularly sensitive developmental window when it comes to our microbiome development, and it has consequences for allergic disease,” concludes Courtney Hoskinson.

“These findings again demonstrate how important it is to be careful when it comes to prescribing systemic antibiotics to infants during their first year,” notes co-senior author Dr. Subbarao. “The findings also point to ways we might treat and prevent eczema. And because eczema is often one of the first signs of broader allergic disease, this may give us insight into how to prevent and treat allergic disease in general.”