New CHILD research provides compelling evidence that breastfeeding influences the composition and function of an infant’s microbiome, which in turn plays a crucial role in that child’s later respiratory health.

The microbiome is the community of beneficial microbes living in and on our bodies, especially in our digestive system or gut. Research is increasingly revealing the crucial role the microbiome plays in human health.

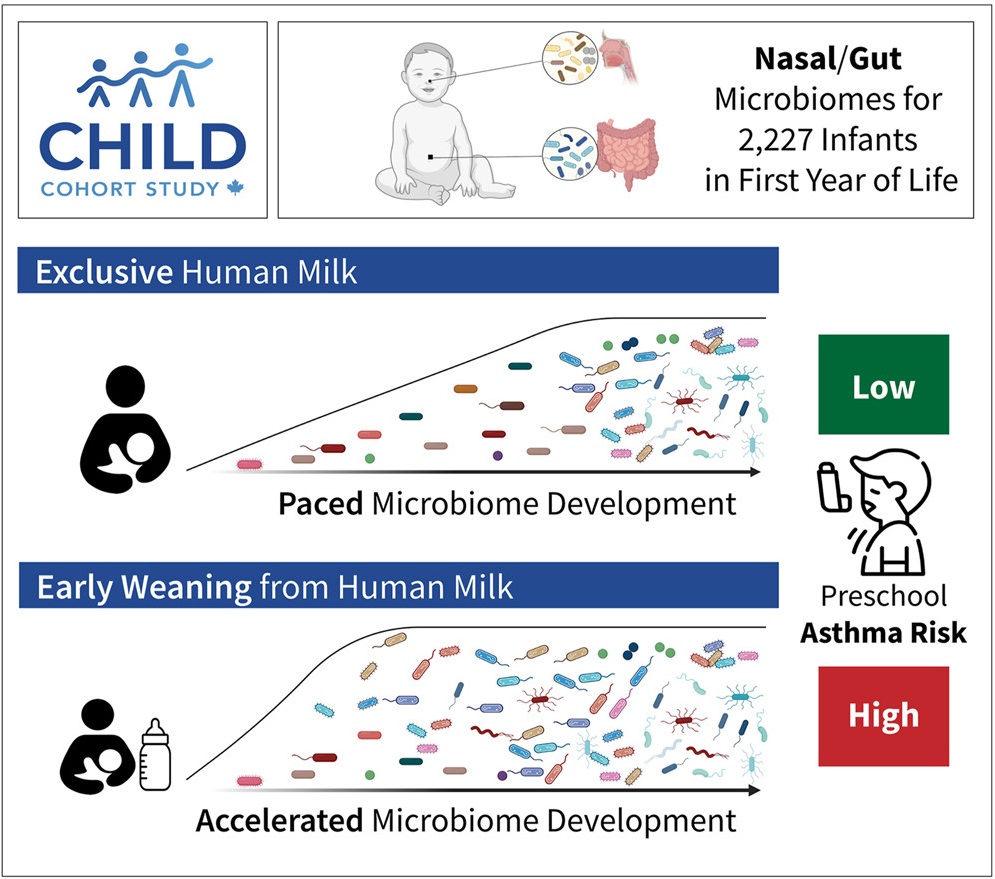

In this study, published in Cell, the researchers examined the nasal and gut microbiomes, breastfeeding characteristics, and breastmilk composition of 2,227 children participating in CHILD. They then compared this information with the children’s respiratory health at three years of age, focusing on whether they had developed “persistent wheeze,” an early warning sign of asthma.

The researchers found that human milk indirectly protects against asthma by regulating nasal and gut microbiome development during the first year of life.

Specifically, the research showed that feeding an infant nothing but breastmilk—exclusive breastfeeding—for the first three months of life supports a well-paced microbiome development, resulting in low asthma risk, whereas weaning from breastfeeding before three months after birth speeds up microbiome development, leading to a higher asthma risk.

Infants who are exclusively breastfed for the first three months develop an abundance of microbes that specialize in breaking down complex sugars in human milk called human milk oligosaccharides. Infants who are weaned earlier than three months become home to a different set of microbes that thrive on the other foods that child is fed. While many of these other microbes eventually end up in all babies, the researchers showed that their earlier arrival is linked to an increased risk of asthma.

Dr. Azad interviewed on CTV News about this research

“Healthy microbiome development is not only about having the ‘right’ microbes—they need to arrive in the right order, at the right time,” explained Kelsey Fehr, Senior Research Technician & Analyst with the Manitoba Interdisciplinary Lactation Centre (MILC) at the University of Manitoba, who was the lead analyst on the study. “Timing is everything, and breastmilk is the pacemaker.”

“These findings strongly suggest that, through its profound impact on the infant microbiome, human milk plays a vital role in long-term respiratory health,” said CHILD Deputy Director Dr. Meghan Azad, co-leader of this research, who is also Director of MILC and a professor at the University of Manitoba, a Research Scientist at the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba (CHRIM), and Canada Research Chair in Early Nutrition and the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease.

“This study also allowed us to identify specific microbial species and functions that are linked to how one’s immune system functions and whether one develops asthma,” added Dr. Azad.

“We found that the bacterial species called Ruminococcus gnavus appeared much sooner in the guts of children weaned early from breast milk compared to those who were exclusively breastfed. This species plays a role in chemical processes known to influence immune system regulation and disruption, including asthma risk.”

“This knowledge could help us to develop new strategies for optimizing infant health and for preventing respiratory conditions from an early age.”

CHILD data also allowed the researchers to distinguish the impact of breastfeeding on an infant’s microbiome from the effect of various other environmental factors, including prenatal smoke exposure, antibiotics, and the mother’s asthma history. Even accounting for these factors, they found that breastfeeding duration remained a powerful determinant for the child’s microbial makeup over time.

They also used their knowledge of these microbial dynamics together with data on different milk components to train a machine-learning model that accurately predicted asthma years in advance. Finally, they created a statistical model to learn causal relationships, which showed that the primary way breastfeeding reduces asthma risk is by shaping the infant’s microbiome.

“The computational methodology we developed provided deep insights into the microbial dynamics and their interactions with the infant host,” comments the other co-leader of the study, Dr. Liat Shenhav, a Computational Biologist at and assistant professor at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, its Institute for Systems Genetics, and the School’s Department of Microbiology. “This interdisciplinary collaboration has paved the way for new discoveries in infant health and developmental origins of health and disease.”

The findings contribute to a growing body of evidence supporting breastfeeding as a key factor in shaping lifelong health.

“This research shows us again how important it is to promote breastfeeding as a public health priority, given its significant benefits for both the microbiome and respiratory development,” concludes Dr. Azad.

Graphical abstract from the publication