In a new study published in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, a research team from The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) has shown that pulmonary function tests are a valuable tool for monitoring children with recurrent wheezing, even in children as young as three years of age.

The paper was selected by the journal as one of three “Editor’s Choice” articles in its August 2020 issue. Dr. Padmaja Subbarao, a staff respirologist at SickKids and the Director of the CHILD Cohort Study, was the study’s senior author.

Recurrent wheezing in early childhood is associated with an increased risk of asthma by school-age and reduced lung function later in life. Asthma can damage a child’s growing lungs and lead to lifelong respiratory problems, so detecting airway changes early is critical so doctors can provide appropriate treatment before lung damage occurs.

Traditionally, monitoring of young children with severe wheezing is based primarily on the report of symptoms by parents. In this study, the researchers found that almost half of children whose parents reported their wheezing symptoms were “well controlled” had abnormal lung function.

“The goal of caring for children with asthma is to ensure their disease is well controlled, and that boils down to both monitoring their symptoms and objectively measuring lung function with pulmonary function tests,” said Dr. Subbarao.

“Our study showed that symptom scores alone are insufficient to give a full picture of what is happening in the airways at this early age.”

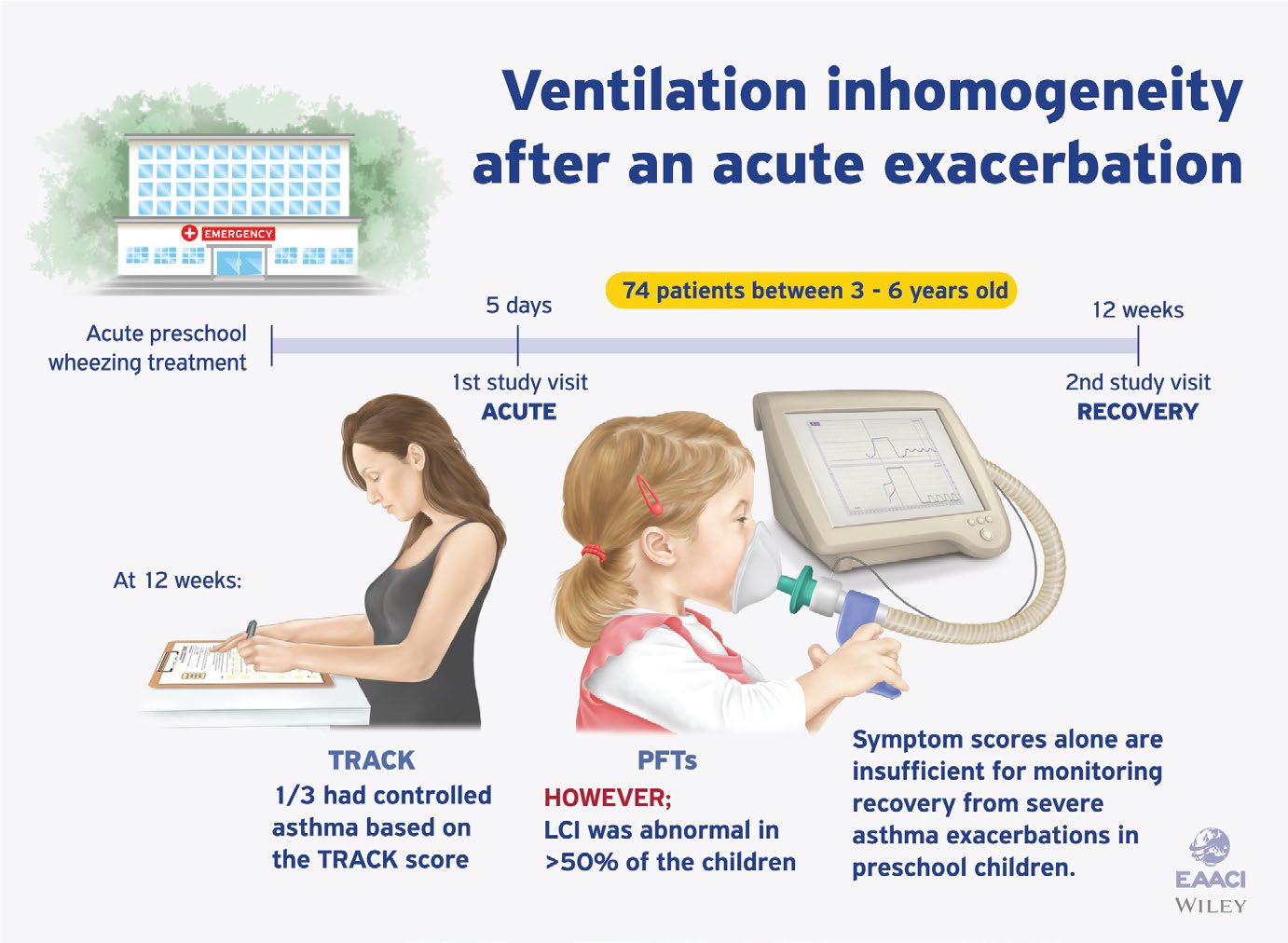

The researchers evaluated 74 preschool children (three to six years of age) with a history of recurrent wheezing in the previous year who were treated for acute wheezing exacerbation in the Sick Kids’ Emergency Department (ED). The researchers conducted two assessments: the first was within five days of the ED visit and the second was approximately three months after the ED visit.

During the assessments, parents completed an asthma symptom questionnaire, and the researchers evaluated the children clinically and conducted pulmonary function tests to measure lung function by forced expiratory volume (FEV1) – a measure of airflow through the airways in one second; and lung clearance index (LCI) – a sensitive marker of physiological changes in the lungs and airways.

The LCI was measured using a technique called the Multiple Breath Washout (MBW), in which the child breathes 100% oxygen, which begins to displace the nitrogen naturally present in air and our lungs. Doctors measure how efficiently the lungs are working by tracking the time it takes the oxygen to “wash out” the nitrogen present in the lungs during normal respiration.

“We found that at their second visit, after recovering from a severe wheezing episode, 40% of the children had abnormal LCI values despite parents reporting good symptom control,” commented Dr. Subbarao.

The study also demonstrated that the LCI test was feasible in the majority (68%) of the children at the second study visit and the test’s success improved with training and the child’s age. “This is important because lung function testing in preschool children in the clinical setting is challenging and the feasibility of a test is critical to improving outcomes,” she said.

“Taken together, these findings suggest that incorporating the LCI test into the monitoring of preschoolers with severe wheezing may provide important clinical information and give insight into the management and care for these children going forward.”