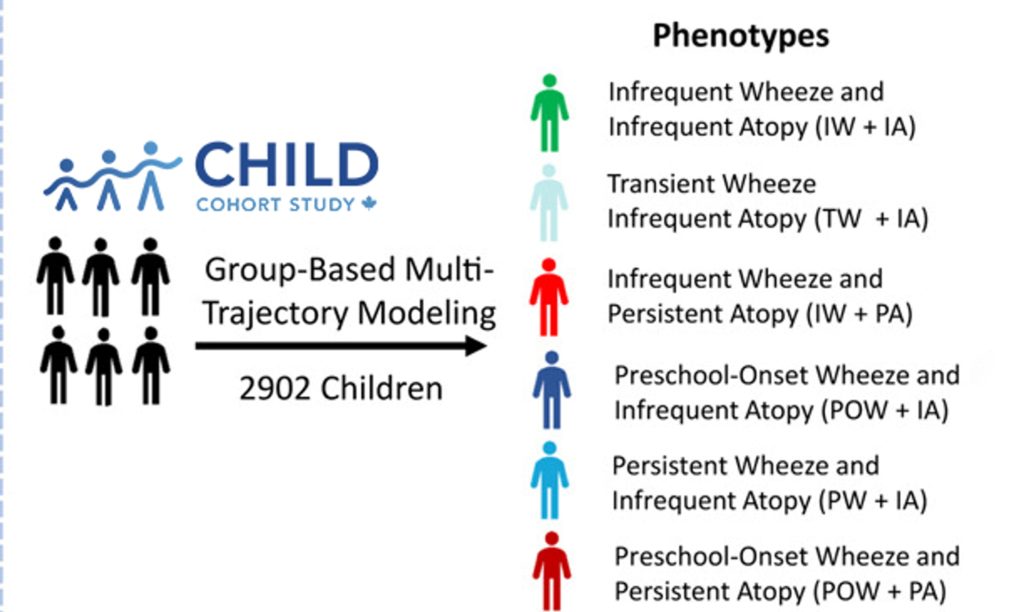

Researchers from CHILD have identified six different categories, or ‘respiratory phenotypes’, of wheeze in preschool children using data collected from birth through age five. Children were grouped based on shared patterns: the age their wheezing began, whether episodes persisted over the years, and whether wheeze was linked to allergies.

The study found that while children with allergic wheeze had the highest individual risk of developing asthma, non-allergic wheeze was far more common—and these children made up the majority of asthma diagnoses and hospital visits by age five.

“Childhood wheeze is a whistling sound from narrowed airways. It is common in young children and can have various causes. Many children outgrow it, but some develop persistent asthma,” notes senior author and CHILD Director Dr. Padmaja Subbarao.

“Not only do we need to know which young kids are most likely to develop asthma, we also need to understand the type of asthma they will develop. Properly characterizing them early is critical for managing their conditions with more precision and efficacy. ”

Published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (JACI), this new research sheds light on the different biological paths that lead to preschool wheezing and asthma.

The researchers analyzed data from over 2900 participants in CHILD. Information included parental questionnaires, allergy and lung tests, healthcare reports, genetic risk scores, and stool samples to study gut bacteria. By combining these measures, researchers found that these six distinct respiratory phenotypes differed by lung function, immune responses, allergy diagnoses, early growth patterns, family history, and environmental exposures. Each type also showed a distinct pattern of gut bacteria at age one.

“Our findings agree with other large studies that have independently found similar wheeze patterns,” says co-lead author Dr. Charisse Petersen and CHILD Deputy Director.

“But what’s unique about CHILD is that we could dig deeper into the biology by integrating multiple measures. For example, the fact that the gut microbiota was already shifted at age one—even before wheeze appeared in some kids—points to early clues that could help quickly identify and support at-risk children. This knowledge moves us closer to treatments designed for each child, instead of relying on a one-size-fits-all approach.”

Doctors are often most alert to wheeze with allergic symptoms, and standard treatments—such as inhaled corticosteroids—are designed for those children. But the study shows that most children belong to non-allergic groups, where these medicines are less effective.

“More than 88% of children with wheeze fit into one of the three non-allergic phenotypes,” comments co-lead author Dr. Zihang Lu, a Biostatistician and Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences at Queen’s University.

“These children accounted for more than 60% of asthma diagnoses by age five, and two-thirds of ER visits and hospital stays for breathing problems.”

“Clinical practice tends to focus mainly on allergic wheeze and to treat wheezing conditions with corticosteroids, which are of little help to non-allergic patients,” adds Dr. Subbarao.

“Our research clearly shows we need to pay more attention to non-allergic wheezers. We urgently need treatments tailored to their needs—to improve their quality of life and to reduce the burden on families and our healthcare system.”