Some research findings out of CHILD grab headlines because they are so readily understandable and clearly applicable to everyday life—like the fact that children born by C-section are more at risk for allergies, or that eating peanut early in life reduces the risk of developing a peanut allergy. Many such findings are featured in CHILD’s Key Discoveries.

However, studies like CHILD produce many other findings that are not as attention-grabbing, but that contribute important knowledge toward longer-term discoveries. Down the line, these incremental findings may lead to major new insights with high impacts on health practices and life choices.

Every year CHILD researchers publish numerous studies of this kind, adding bricks to the always growing edifice of scientific knowledge.

Below is a summary of contributions made by CHILD research in 2023 and the first few months of 2024, organized by general topic. Thanks to the ongoing commitment of CHILD families, this proudly Canadian birth cohort continues to advance science in many different directions!

Asthma & Allergies

Recent CHILD research has shed light on how machine learning (a form of artificial intelligence) can be used to predict asthma; how different factors (including socio-economic status, exposure to green spaces, use of gas stoves in the home, and microbiome maturation) influence asthma and/or allergy risk; and the gene-level impact of introducing allergenic foods early.

CHILD researchers used various machine learning models to find that childhood asthma is predictable from non-biological measurements, mainly using parental asthma and the patient’s medical history in terms of wheezing, allergic sensitivity, antibiotic exposure, and infections in the lower respiratory tract. This insight could lead to early risk identification and preventative action.

Data from CHILD and other cohorts were used to determine that children in lower-income communities are at higher risk of developing asthma and allergic disease. These findings have implications for policymakers, so they can address associated healthcare needs and contributing environmental factors, and for healthcare providers and educators, so they can help equip affected families with disease management strategies.

CHILD research in Edmonton, Alberta, found that living close to a natural green space generally protects children from developing asthma or allergies, with implications for policymakers and city planners regarding the importance of preserving natural green space in urban areas.

Another study—the first of its kind in Canada—leveraging CHILD data found that the use of gas stoves may increase asthma risk, depending on other factors like whether an exhaust hood is used or whether windows are kept open while cooking. The study findings suggest replacing a gas stove with an electric one may be advisable, especially in households with people who already have asthma or other breathing challenges.

CHILD researchers also found that a delay in the maturation of an infant’s gut microbiome—that is, when it takes longer for an infant to develop a rich, diverse community of microorganisms in their digestive tract—can lead to a greater risk of developing childhood allergies, including asthma, allergic rhinitis, food allergy, or atopic dermatitis (eczema). This finding may enable the better prediction and prevention of allergic disease.

CHILD data were also used to show that neither developing a sensitivity to certain highly allergenic foods (like egg, cow’s milk and peanut), nor being introduced early to these foods, has an effect on children’s DNA methylation—that is, the process by which certain gene functions are turned on or off. This knowledge furthers our understanding of what goes on in our bodies when it comes to developing or avoiding allergies.

Other studies out of CHILD mentioned below showed that breastfeeding protects against the development of asthma even when the mother’s milk contains fewer sugars due to her genetic make-up, and that exposure to air pollution while in the womb increases asthma and allergy risk.

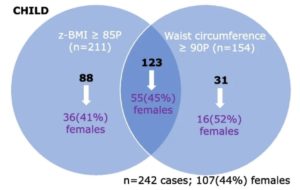

Overweight | Obesity | Growth

Recent CHILD research has explored the relationship between body mass and other factors, including delivery method, gestational age at birth, fungi living in the infant gut, and sex-based differences in children’s metabolism.

CHILD found that delivery by C-section, especially if no labour was involved, leads to a higher risk of obesity, and that the degree of risk differs between girls and boys. This finding may help identify children at risk of becoming overweight, to help them find strategies toward maintaining a more health-sustaining body weight.

CHILD data contributed to an international study (Europe, Australia and Canada) that found gestational age at birth impacted body size in infants (babies born earlier tend to be smaller), but that this difference lessened as children age (early-born kids catch up in size with their later-born peers as the years go by).

Another CHILD study found that whether infants have a diverse, rich colony of fungi living in their digestive tract influences how quickly or slowly they grow. Previous studies tended to focus only on the role of gut bacteria (microbiome); this study suggests more attention should be paid to gut fungi (mycobiome).

Using state-of-the-art methods to analyze CHILD biological samples, recent research also identified specific metabolic chemicals in human blood—that is, chemicals used by the body to convert food into energy—that influence whether a person is likely to become overweight or obese. A specific pattern of metabolic chemicals was associated with a greater risk of later obesity; this association was especially strong among girls. Knowing this may allow earlier interventions to help people avoid becoming overweight.

Other recent studies out of CHILD mentioned below showed that showed that breastfeeding protects against the development of obesity even when the mother’s milk contains fewer sugars due to her genetic make-up, and that if a mom smokes while pregnant it increases her child’s risk of obesity.

Gut | Microbiome

CHILD research has been among the first to highlight the importance to our health of the community of bacteria living within us (the human microbiome). The Study continues to expand our insights into the microbiome. In recent months, CHILD has shed light on the interrelationships between microbiome development, birth delivery method, and an infant’s diet, including vitamin intake and breastfeeding.

One study by CHILD researchers looked at what influences different patterns of gut microbiome development, and they found that whereas formula feeding and C-section delivery impacted bacteria in the gut, fungi in the gut were effected instead by the consumption of artificial sweeteners – and by gut bacteria. These findings contribute to our understanding of what risk factors impact the development of a healthy microbiome, allowing for strategies to address these risks.

Another study looked at data from CHILD and other birth cohorts to find that whether an infant is breastfed or formula-fed has a significant effect on the composition of their gut microbiome, as well as on the metabolic chemicals in their blood. The finding suggests that formula-fed infants may need other interventions to help ensure their microbiome develops well.

Two other studies out of CHILD found that giving an infant vitamin-D supplements influences the development of their microbiome; and that delivery mode (c-section versus vaginal) and breastfeeding also impacts the gut microbiome in infants, which, in turn, effects the presence of certain naturally-occurring, protective antibodies in the intestine. Again, these studies further illuminate what life choices encourage a healthy microbiome, and how the microbiome influences our broader health.

Maternal factors

CHILD differs from some other birth cohorts in that it follows not only the children born at the outset of the study, it also gathers information about both parents. This allows researchers to explore how the parents’ genes, environment and life choices impact their own health and their child’s health. In recent months, CHILD research showed how Canadian moms are doing when it comes to meeting dietary recommendations during pregnancy; what medications they are taking while lactating; and how smoking while pregnant increases a child’s risk of obesity.

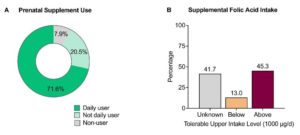

CHILD data recently showed that, during pregnancy, Canadian moms are typically taking more folic acid, and not as much choline, as recommended. This suggests the need for a better understanding of high folic and low choline intake during pregnancy, to determine if educational outreach to physicians and parents is needed to address this trend.

CHILD researchers also recently found that 40% of Canadian moms use medication when breastfeeding their infants, including off-label drugs that are supposed to help with lactation. Given that these medications can be carried in breastmilk and impact the baby, this finding suggests that moms may need more education on this topic; the findings also suggest that a commonly used off-label lactation medicine (domperidone) should be better studied to determine how effective and safe it is.

CHILD research further demonstrated that if moms smoke during pregnancy it increases the risk of her child becoming obese, most likely because of certain effects smoking has on the microbiome. If moms quit smoking before pregnancy this effect was avoided, but not if they quit once already pregnant. If moms who smoked exclusively breastfed their infants, on the other hand, this seemed to lower the risk. These findings add to the evidence that women should quit smoking before their pregnancies to prevent microbiome-mediated childhood overweight and obesity risk.

Research mentioned in other sections here further shows the impact of maternal exposure to air pollution during pregnancy on an infant’s allergy and asthma risk; and the impact of maternal mental health (together with other factors) on child behaviour.

Breastmilk | Breastfeeding

CHILD has contributed significantly to global knowledge about the benefits of breastfeeding and about the special qualities of human milk. In recent months, related learnings from CHILD touch upon: what mental health factors impact breastfeeding and how this, in turn, impacts child behaviour; the relationship between fatty acids in milk and a mother’s heart health; how breastfeeding protects children against asthma and overweight even when moms’ milk is different because of their genetic make-up; and how human milk works as a biological system.

CHILD researchers found that postpartum depression and dysfunction in parent-child relationships negatively impacted breastfeeding and child behaviour. The findings suggest that encouraging breastfeeding and better supporting parental mental health and parent-child relationships may help to improve child behavior.

Another study using CHILD date found that there are clues in the composition of a mother’s milk that help to predict whether that mom will develop cardiometabolic disease. This finding offers a new tool for the diagnosis and early treatment or prevention of heart disease in women.

CHILD had already shown that sugars in breastmilk enrich a child’s gut microbiome and this helps protect that child from allergies, asthma and obesity. However, it was not known if milk from moms with a particular gene (FUT2, which effects the production of milk sugars) had the same protective quality. A new CHILD study found that the milk of moms with this gene is equally beneficial to infants, suggesting these moms should be equally encouraged to breastfeed for the benefit of their children.

Research using CHILD data also looked at how proteins and peptides in human milk contribute to the way milk benefits newborns and promotes healthy development. This finding offers a doorway to further investigations into the role of these particular components of milk.

Research mentioned in other sections here further discusses medication use by Canadian moms while breastfeeding, the impact of formula feeding on the microbiome, and how breastfeeding encourages the development of protective antibodies in the gut.

Other Findings

CHILD data is so comprehensive, and the biological samples the Study collects are so rich in potential information, that CHILD is allowing scientists to explore many more things beyond the original focus of the study, on asthma and allergies. Already the summaries above show some of the diversity of CHILD-enabled research findings. A few more recent findings cover the additional topics of heart health, the health effects of air pollution and house dust, and issues related to COVID.

A study using CHILD data found certain genetic patterns among people with a particular heart condition (cardiomyopathy), adding to the toolbox for diagnosing and potentially treating this condition.

CHILD researchers found that babies exposed to air pollution while in the womb experience gene-level effects that increase their risk of developing allergies and asthma, adding to evidence that avoidance of traffic pollution, and government regulation to minimize pollution, are advisable.

Studies of house dust collected from CHILD family homes showed that a certain health-impacting chemical (a phthalate) is more common in lower-income households and is increased by the presence of vinyl flooring and furniture as well as mold; and that the presence of certain flame-retardant chemicals in house dust has a negative impact on the mental health of pregnant moms and moms with newborns. Both point to the need for informational and regulatory interventions to minimize the introduction of these chemicals into Canadian homes.

CHILD’s COVID add-on study found that government programs to promote mask use during the COVID pandemic were effective: government-mandated mask use and providing the public with up-to-date health information was associated with increased compliance. This supports the ongoing use of mask mandates and educational campaigns in Canada if we should be confronted again by a pandemic threat like that of COVID.

This brief survey of publications emerging from CHILD over the last 15 months shows what a wealth and diversity of knowledge is regularly being generated from the Study’s data and by researchers within and beyond CHILD. While more high-profile CHILD findings will undoubtedly reach you before long through online headlines and other media, in the meantime CHILD continues accumulating knowledge and evidence that will enable more scientific and health breakthroughs in the future.