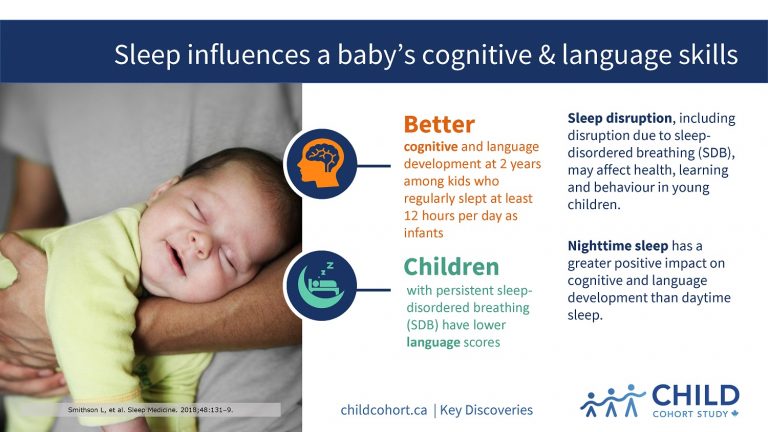

Sleep influences a baby’s cognitive & language skills

Does your child sleep less than 12 hours over a 24-hour period? Does he or she breathe through the mouth, snore or have pauses in breathing while asleep?

If the answer to either question is yes, findings from CHILD explain how sleep disruption may affect health, learning and behaviour in young children.

In a pair of studies by Dr. Piush Mandhane (University of Alberta), lead of CHILD’s Edmonton site, CHILD researchers examined the impact of an infant’s sleep duration and disruption due to sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) on cognitive and language development at two years of age, and identified four distinct types of SDB that occur in infants, along with unique risk factors associated with each.

LESS SLEEP, POORER DEVELOPMENT

In the first study, published in Sleep Medicine, Dr. Mandhane’s team found that infants who regularly sleep less than 12 hours total over any given 24-hour period have poorer cognitive and language development at two years of age than infants who get more sleep.

They also found that nighttime sleep had a greater impact on cognitive and language development compared to daytime sleep, and a short nighttime sleep was associated with a 10.1-point decrease in cognitive development using a standardized test of mental and motor development.

“A drop of 10 points represents nearly a full standard deviation on the cognitive scale,” explains Dr. Mandhane. “It’s quite a substantial difference.”

The researchers further found that children with persistent SDB had lower language scores, but no differences in cognitive development compared to children with no SDB.

There are a few possible explanations for this finding, according to Dr. Mandhane. “One theory is that language acquisition is more sensitive to sleep disruption than cognitive development,” he says.

“Alternatively, the link between SDB and language delay may be the result of kids having multiple nose and ear infections, which tend to impair hearing and speech.”

SNORING VARIATIONS

In the second study, the researchers delved into the children’s snoring patterns, hoping to find out if there were different types of snorers and what factors might be influencing them.

They identified four patterns of SDB from infancy to two years of age: i) no SDB; ii) early-onset SDB with peak symptoms at nine months of age; iii) late-onset SDB with peak symptoms at 18 months of age; and iv) persistent SDB with symptoms from three to 24 months.

Infants given acid reflux medication were more likely to have early-onset SDB, while children who were exposed to smoke or dogs in the home were more likely to develop late-onset SDB, the study found.

“We also found that children at risk for allergies or with divorced parents were more likely to present with persistent SDB,” comments Dr. Mandhane.

THE IMPORTANCE OF SLEEP

“Together, these findings highlight the importance of total and nighttime sleep, and demonstrate the cognitive and language problems that can occur in preschool children when sleep is disrupted,” Dr. Mandhane says.

“Our results suggest that early intervention to reduce specific SDB risk factors may help to avoid more serious behavioural, cognitive and emotional problems down the road.”